SOVEREIGN ASSETS & IRON HOOVES: INSIDE TURKMENISTAN’S EQUINE TRINITY

In the high-stakes world of global equine trade, a horse is rarely just an animal; it is a financial instrument, a vessel of cultural memory, and in some cases a tool of statecraft, so while to the uninitiated a horse is simply a horse, there are different types of horse economies which I will call the “Big Three”: the Thoroughbred, the Arabian, and the Akhal-Teke direct from Turkmenistan; each representing three fundamentally different economic systems governed by distinct rules of liquidity, valuation, and purpose. The Thoroughbred dominates Western headlines, the Arabian anchors elite prestige in the Middle East, and a third, more enigmatic model emerges deep in Central Asia, where understanding the horse economy of Turkmenistan requires abandoning the mindset of a trader and adopting that of a geopolitical strategist, because here the horse is not a commodity but a sovereign asset.

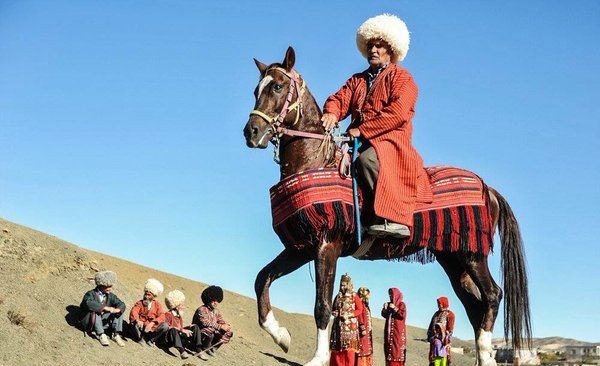

Where is Turkmenistan and what is the Akhal-Teke?

Turkmenistan, a landlocked nation in Central Asia bordered by the Caspian Sea, Iran, Afghanistan, and Uzbekistan, and dominated by the vast Karakum Desert, is a country with a rich tapestry of history, culture, and tradition shaped by nomadic heritage and Silk Road trade routes. Though often overlooked on the global stage, Turkmenistan’s identity is deeply intertwined with its equestrian legacy, where horses are more than just animals; they are symbols of pride, endurance, and national character. Over centuries, the Turkmen people cultivated a distinctive equine culture adapted to the harsh desert environment and migratory life, resulting in some of the world’s most remarkable horse breeds. Today, horse imagery permeates Turkmen art, national emblems, and celebrations, reflecting a cultural reverence that transcends sport or commerce and connects modern Turkmen citizens with their ancestral past.

At the heart of this equestrian heritage is the Akhal-Teke, one of the oldest and rarest horse breeds in the world, renowned for its ethereal beauty, endurance, and unique metallic sheen that gives it the nickname “golden horse.” Bred for more than two and a half millennia in the arid steppes and deserts of Turkmenistan, Akhal-Tekes combine speed, stamina, and intelligence in a way unmatched by most other breeds, traits that historically made them prized cavalry mounts and desert companions. While the often-cited “three millennia” emphasises historical continuity, archaeological and historical evidence supports roughly 2,500–3,000 years of selective Turkmen horse breeding as the core lineage of the Akhal-Teke.

Their sleek, long-necked bodies and shimmering coats that range from gold to silver, bay, and gray are the result of generations of adaptation to extreme climatic conditions. Scientifically, this shimmer is caused by a unique hair structure: the opaque medulla (core) of the hair shaft is either greatly reduced or entirely absent. This allows the hair to act as a "light-pipe," refracting light through the transparent cortex and creating a metallic glow that reflects harsh desert UV rays. While loyalty and spirited behavior are culturally attributed, these traits are also influenced by handling, training, and environment. The Akhal-Teke remains a potent symbol of national identity and continuity, embodying a legacy of resilience that continues to captivate equestrian enthusiasts around the globe.

The Thoroughbred - The Engine of Liquidity:

The Thoroughbred economy is the most liquid and transparent equine system ever created, anchored by racing jurisdictions such as the United States, the United Kingdom, Ireland, Japan, Australia, and Hong Kong, and functioning as a mature, multibillion-dollar industry in which auctions at Keeneland, Tattersalls, and Fasig-Tipton resemble financial exchanges, complete with speculative bubbles, market corrections, and data-driven price discovery. Value is determined by performance metrics such as race results, earnings indexes, black-type pedigrees, and stallion statistics, so that a colt’s worth can rise or collapse in a single afternoon, with horses syndicated, insured, leveraged, and traded with a ruthlessness familiar to Wall Street, making a horse in Kentucky or Newmarket an asset with a measurable return on investment.

The Arabian - The Currency of Social Capital:

The Arabian horse operates on a fundamentally different logic. Although endurance racing and sport disciplines play a role, the primary driver of value is social signaling, as beauty competitions or halter shows reward symmetry, expression, and lineage rather than athletic output. Ownership itself confers prestige, so while liquidity exists in this ecosystem, utility often takes a back seat to symbolism. Bloodlines are curated like royal genealogies, and horses are exchanged among elite families, state studs, and private collectors (particularly in the Gulf), making the Arabian a luxury good, closer to a handcrafted watch than a racehorse, whose value lies in what it represents rather than what it produces. While performance can influence international endurance racing value, social prestige and pedigree remain the primary determinants of price.

The Akhal-Teke - The Sovereign Asset:

Then there is Turkmenistan... where the Akhal-Teke does not participate in a free market at all but exists within a command economy structured around national identity. Officially designated a “National Treasure,” it is overseen by the State Association Türkmen Atlary, which controls breeding approvals, studbook registration, and exports. The most valuable bloodlines remain firmly under state ownership, elite stallions are not sold but retained for national studs, presidential stables, and ceremonial use, and horses are only occasionally gifted to foreign leaders rather than commercialized. This deliberate restriction of supply creates artificial scarcity by design rather than by accident.

The Liquidity Trap and the Tenfold Price Gap:

This system produces one of the most distorted equine markets in the world. Domestically, Akhal-Tekes used for riding, local sport, or breeding may sell for relatively modest sums, typically between $5,000 and $15,000, reflecting local demand and the limited purchasing power of private buyers. Internationally, however, prices can increase tenfold or more, with export buyers routinely paying $50,000 and, in some cases, exceeding $100,000 for elite bloodlines.

The disparity is driven not by differences in genetic quality but by institutional and regulatory friction: exporting an Akhal-Teke requires state approval, extended quarantine periods that can last several weeks, compliance with cultural heritage safeguards, and adherence to Turkmenistan’s strict export protocols, meaning buyers are often paying as much for access and bureaucratic clearance as for the horse itself. Compounding this dynamic is a persistent “registration discount”: unlike Thoroughbreds, whose documentation and pedigrees are universally recognized, Akhal-Tekes suffer from fragmented registry legitimacy, stemming from historical disagreements between Turkmen authorities and international studbooks, which can result in horses without fully harmonised papers facing valuation penalties of 30 to 50 percent in overseas markets.

Beyond the Gold - The Yomut and the All-Terrain Horse:

While the metallic sheen of the Akhal-Teke captures global attention, Turkmenistan’s equine heritage is far more diverse. Along the southeastern Caspian coast, the Yomut tribe developed a horse built not for ceremony, but for survival. One of the five major Turkmen tribes, the Yomut historically divided between settled farmers and nomadic herders, and their horses reflect this duality: honed over centuries through selective crossing with Arabian blood, the Yomut horse was bred for endurance, adaptability, and self-reliance. Standing a compact 14 to 15 hands, the Yomut is renowned for its exceptionally hard hooves, capable of traversing desert sands and rugged mountain terrain unshod, and for its genetic diversity, which produces both slender endurance types and stockier variants used to reinforce northern breeds. In 1935, Yomut horses famously undertook the legendary Ashgabat–Moscow ride, covering over 4,300 kilometers, a testament to their stamina and resilience. In an era of climate uncertainty, the Yomut embodies a blueprint for biological adaptability, and within Yomut culture, a horse is far more than property- it is blood, a living extension of the people themselves.

The Goklan and the Mountain Horse:

Beyond the five tribal emblems on Turkmenistan’s flag lies the often-overlooked Goklan, historically situated between the steppes and the Kopet Dag mountains, where they developed a horse uniquely adapted to steep terrain, harsh climates, and heavy labor. The Goklan horse is considered the most robust descendant of the ancient Turanian type: muscular, short-backed, and powerfully built, able to carry heavy loads and navigate mountain passes where lighter breeds falter. Traditionally bred for transport, mountain riding, and agricultural work, the Goklan embodies the Turkmen concept of namys (honour), prioritising reliability, strength, and resilience over elegance or showy appearance. Today, the breed persists largely outside commercial markets, maintained by rural herders and tribal families, serving as a living reminder of pre-modern equine utility and the deep connection between Turkmen communities and their working horses.

A Global Comparison:

Placed side by side, the contrast among the world’s major horse economies is striking. Thoroughbreds are engineered for liquidity, performance, and revenue, their value measurable in earnings, stud fees, and auction results. Arabians operate in the currency of social capital: their worth is tied less to athletic output than to beauty, lineage, and the prestige they confer upon their owners. Turkmen horses, led by the Akhal-Teke and reinforced by tribal breeds like the Yomut and Goklan, follow a wholly different logic, one of sovereignty, continuity, and resilience. Unlike the Thoroughbred, optimized for speed and ROI, or the Arabian, prized for elegance and pedigree, the Akhal-Teke is embedded in the national identity of Turkmenistan, carefully managed by the state, and intentionally insulated from market forces. Tribal horses extend this paradigm: the Yomut embodies adaptability and endurance across deserts and mountains, while the Goklan demonstrates strength and reliability in rugged terrain. These horses are not designed to scale or generate profit; they are maintained to preserve bloodlines, uphold cultural values, and safeguard biological resilience. In short, where global horse markets chase liquidity or prestige, Turkmenistan’s equine ecosystem asserts a different metric of value entirely: strategic continuity, cultural heritage, and sovereign control.

The Investment Verdict:

For modern investors, the Turkmen horse offers no easy returns. There is no betting economy, no standardised prize structure, and no frictionless exit strategy; instead, value is measured in scarcity, symbolism, and cultural capital. Turkmenistan’s horse economy is not underdeveloped - it is intentionally non-commercial, a system designed to safeguard heritage, bloodlines, and national prestige rather than generate profit. In a world increasingly dominated by homogenized markets, this deliberate refusal to commodify represents its own unique form of power. As a Turkmen proverb reminds us, “After the father, the horse is the most important.” In Turkmenistan, that importance is not calculated in dollars or market indices; it is preserved in legacy, lineage, and sovereignty, making the horse both a living symbol and a strategic national asset.

For those deeply committed to owning an Akhal-Teke despite Turkmenistan’s restrictive export regime, there are viable pathways on the international marketplace, though they require patience, connections, and often substantial investment. While direct export from Turkmenistan remains tightly controlled and limited to occasional state-approved transactions, Akhal-Teke populations have been established in Russia, Kazakhstan, Europe, and North America through historical breeding programs and private associations, allowing interested buyers to purchase outside the Turkmen state framework. In Russia and Kazakhstan, reputable stud farms maintain purebred lines with documented pedigrees and occasionally offer horses for sale, with prices influenced by age, training, and lineage. In Europe, breeders in countries like France, Estonia, Germany, and others list Akhal-Teke horses through specialized networks, sometimes making them available for export to other regions with proper health clearances. In North America, organizations such as the Akhal-Teke Association of America maintain breeder directories that can help potential buyers connect with legitimate sources, and horses there often come with standardised registration recognized by international associations. Prices outside Turkmenistan vary widely: young foals may start in the €10,000 range, while well-trained adults with exceptional lineage can exceed €50,000 or more, reflecting both rarity and the costs of international transport and compliance with import regulations. This global network provides a practical alternative for collectors and enthusiasts seeking these iconic “golden” horses, balancing desirability with the realities of legal, health, and logistical hurdles inherent in cross-border equine acquisition.

--ENDS--

About the Author:

Christopher Wizda, a member of ASEEES (Association for Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies), is an international development and education specialist with over a decade of experience across Eurasia, including Turkmenistan, Mongolia, and Russia. He has led programmes for NGOs, UN agencies, and government-adjacent organisations, focusing on capacity building, community development, and strategic planning. Fluent in Russian and experienced in Mongolian and Turkic languages, he leverages regional expertise and cross-cultural insight to advance sustainable development and institutional strengthening. He is currently conducting specialised research on Turkmenistan and Turkmen culture.